September 2020 | 1756 words | 7-minute read

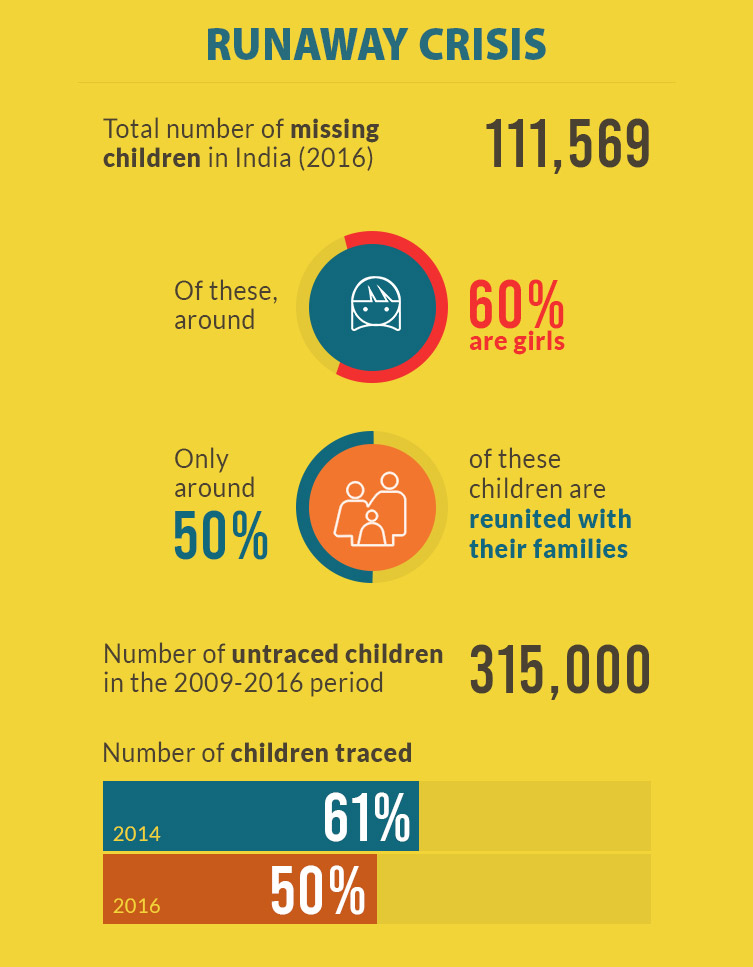

About 250,000 children in India went ‘missing’ or ran away from their homes between January 2012 and March 2017. That statistic, from the Indian government’s ‘track child’ portal, means five children disappear every hour in the country.

Finding these children — oftentimes rescuing them — and reuniting them with their families is the challenge taken on by Society for Assistance to Children in Difficult Situation (SATHI), which has a steadfast supporter in the Tata Trusts. A Bengaluru-based nonprofit set up in 1992, SATHI has, in the years since, helped some 77,000 kids get back to their families.

SATHI has worked in 45 locations in 14 states, mainly with children who have run away from their homes or have been separated from their families and end up at railway stations. It operates four temporary shelters (in Delhi, Varanasi, Kanpur and Pune) that come under the ‘open shelter’ project in the Indian government’s Integrated Child Protection Scheme.

Finding these children is the first step in an endeavour that constantly faces multiple complexities. SATHI then provides them care at a shelter, guidance and counselling before, in its words, “making an attempt to reunite the child with [his or her] family”.

Children who run away from home or lose contact with their families face a life of hardship and, frequently, abuse. Many are victims of abduction and human trafficking. Their families, for their part, suffer the trauma of separation and loss, made worse by the reality that the chances of seeing their child again are slim.

Shahrukh's story

“I was playing at the railway station near my home when a stranger approached me. He asked me to come with him to see famous places in Delhi. He also offered me work. I agreed because I wanted to see Delhi. But after we went to Jama Masjid, he left me.”

This is what 12-year-old Shahrukh told the SATHI counsellor in New Delhi in september 2018 after someone called the ‘railway childline’ and he was picked up from the Jama Masjid area. But certain pieces seemed not to fit. A stranger entices a child and then abandons him?

The SATHI team spent time talking to Shahrukh, asking about his family, about his parents, his siblings… Finally, the boy spilled the beans.

Shahrukh’s home – where he lived with his parents, two brothers and three sisters – was in Shamli district of Uttar Pradesh. His father was a labourer and his mother a homemaker. He had run away to explore famous places in Delhi. The Shamli railway station was close to his house and he boarded a train to Delhi.

The stranger Shahrukh spoke about was actually a fellow passenger in the train who, on seeing a lonely child, had tried to help. He took Shahrukh to Jama Masjid because the child said he lived there. As he seemed confident about returning ‘home’ on his own, the man left Shahrukh to his own devices.

The only telephone number Shahrukh knew was that of a teacher at his village school. It took several days for the SATHI team to connect with the parents and speak to them. Shahrukh stayed for 18 days at the shelter before his overjoyed father came to take him back home.

Many reasons for taking off

Children run away for many reasons, says Abhijeet Nirmal, manager, child protection and anti-human trafficking, with the Tata Trusts in Delhi. “It could be fear, domestic violence or failing in a school exam,” he says. “It might even be the dream of a better life in a big city.”

SATHI’s journey in rehabilitating children started at a time when the standard practice was to place these kids at government-run shelters. “Everyone assumed that there was some serious cause that led to children running away; consequently there was hardly any attempt to trace their families,” says Pramod Kulkarni, SATHI’s founder.

The flaw in the approach was made evident by the fact that many of the rescued children ran away from the government shelters they were forced into. That’s when SATHI began to follow the more difficult process of tracing the families of the children. This went against conventional thinking.

“We were criticised and funding agencies were apprehensive,” says Mr Kulkarni. “The feeling was that the child was being put back into the problem. But we felt that this was a Western view of looking at things. In India family relations are much stronger.”

Even without such issues, child rescue is a thorny undertaking, probably among the toughest in social work. Practical wrinkles aside, there is the legal maze and endless government processes that have to be tackled. Given that SATHI spends much of its energy and resources with children who have somehow made railway stations their home, there are other problems as well.

Railway stations as homes

The railway station-as-home factor is common to countless runaway and other children. And there is Indian Railways, far-flung, ubiquitous and cavernous enough for them to travel by anonymously (mostly without tickets). The children, the majority of them without any fixed destination in mind, tend to get off at a big station or terminus and look for ways to settle in.

That is the best time for an intervention, but even if this is a success there are jurisdiction issues. The railways come under the central government, whereas the police are part of the state’s apparatus. Both have to be kept in the loop.

SATHI toiled for long to get the support of the central and state governments to minimise the processes and paperwork that child rescue operations entail. In 2010, formal mechanisms started being put in place to rescue children from railway stations. That means outreach, an understanding of child psychology and collaboration with several local authorities.

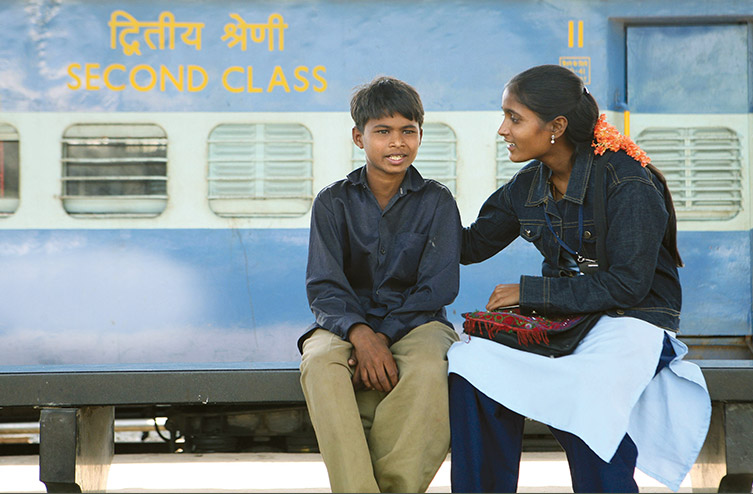

Advocacy by SATHI and likeminded nonprofits resulted in the Indian government’s Ministry for Women and Child Development and Indian Railways coming together to launch ‘railway childline’, a programme to find missing and runaway children. Since then the numbers of runaway children rescued from India’s railway stations and rehabilitated or restored to their families has jumped from less than 5,000 a year to nearly 30,000 a year.

SATHI focuses on big railway stations in the metros. “We look for children who are alone, crying or seem uncomfortable,” says Mukesh Yadav, an outreach coordinator with the organisation. His team operates out of a room provided by the Railway Protection Force (RPF) at New Delhi station. The team works closely with RPF staff and also enlists the help of luggage porters, platform vendors and others who can be their “eyes and ears”.

Abhishek Sharma, who operates a water-dispensing machine at New Delhi station, is one such resource. He recounts an incident where he chanced upon two boys, aged four and six, wandering about looking lost. “The elder one had an Aadhaar card [government-issued identification] and that enabled us to trace his address to an east Delhi locality,” he says. The second child was taken under its wing by SATHI and later reunited with his parents.

Time is of the essence when dealing with runaway and missing children. “The sooner they are rescued, the better,” explains Mr Nirmal. “This ensures they are not influenced by someone with bad intentions, dragged into substance abuse or trapped by traffickers. The child is at its most vulnerable at this point. If someone offers help or food, they accept it instantly.”

Human traffickers keep an eye out for these at-risk children. “In return for free food and a place to sleep, they make them work as bonded labour or push them into prostitution,” adds Mr Nirmal. “Reaching out to children who have been on the streets for longer is a bigger challenge. They have invariably been duped or abused and don’t trust anyone.”

Hub for traffickers

As with everything to do with India, the numbers can be overwhelming. “Over half a million people visit New Delhi station every day and this is a major hub for traffickers,” says RPF inspector Omprakash Rawat. “On average, five or six runaway children are intercepted here every day.”

Once a runaway child has been picked up, the SATHI team follows a streamlined process before having the kid placed at its shelter. Once there, the children follow a regular routine, are provided food and clothes, and get to sleep on a clean bed. They also receive counselling and are kept engaged in a variety of activities.

Finding parents or family is among the toughest challenge facing SATHI because many of the children cannot tell where they are from. Once the child is rehabilitated, SATHI goes a step further. It follows up on some of the more vulnerable children and periodically sends personnel to check on how they are faring at home.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to child rescues. Not all children are willing to return to their parents, especially those addicted to drugs or part of criminal gangs. “In such cases, we take them for a 30-day residential camp outside the city, after which we try and reconnect them with their families,” says Basavaraj Shali, SATHI’s chief executive.

Self-sustaining is the call

As for the future, the Tata Trusts see the SATHI model as one that has to be scaled up further to be effective. “We are trying to pull away to make the model self-sustaining,” says Mr Nirmal. For this to happen, the government needs to step in with financial support.

“The railway childline helps around 20,000 children every year, but the number of missing children landing up at railway stations could be 80,000 a year,” says Mr Kulkarni. It costs `5,000-6,000 to help one child, and he believes that in two years close to full coverage should be possible.

That would take an annual budget of around Rs. 500 million. As of now that budget is Rs. 170 million, distributed among the roughly 100 NGOs operating across India in this field. “This is evidently too little,” says Mr Kulkarni. “Ultimately, child rescue is the responsibility of the government and the project should be funded by them.”

The sooner this and other forms of support are extended, the better it will be for the numerous children who have gone off the radar in India.

Source: Tata Trusts' Horizons, September 2019 issue