December 2019 | 951 words | 4-minute read

Having a literacy rate of 66.41%, the state of Jharkhand is a laggard in education; it’s worse still in Khunti, a district where tribal communities predominate. Improving learning outcomes in school is vital for these communities to climb out of poverty and ignorance.

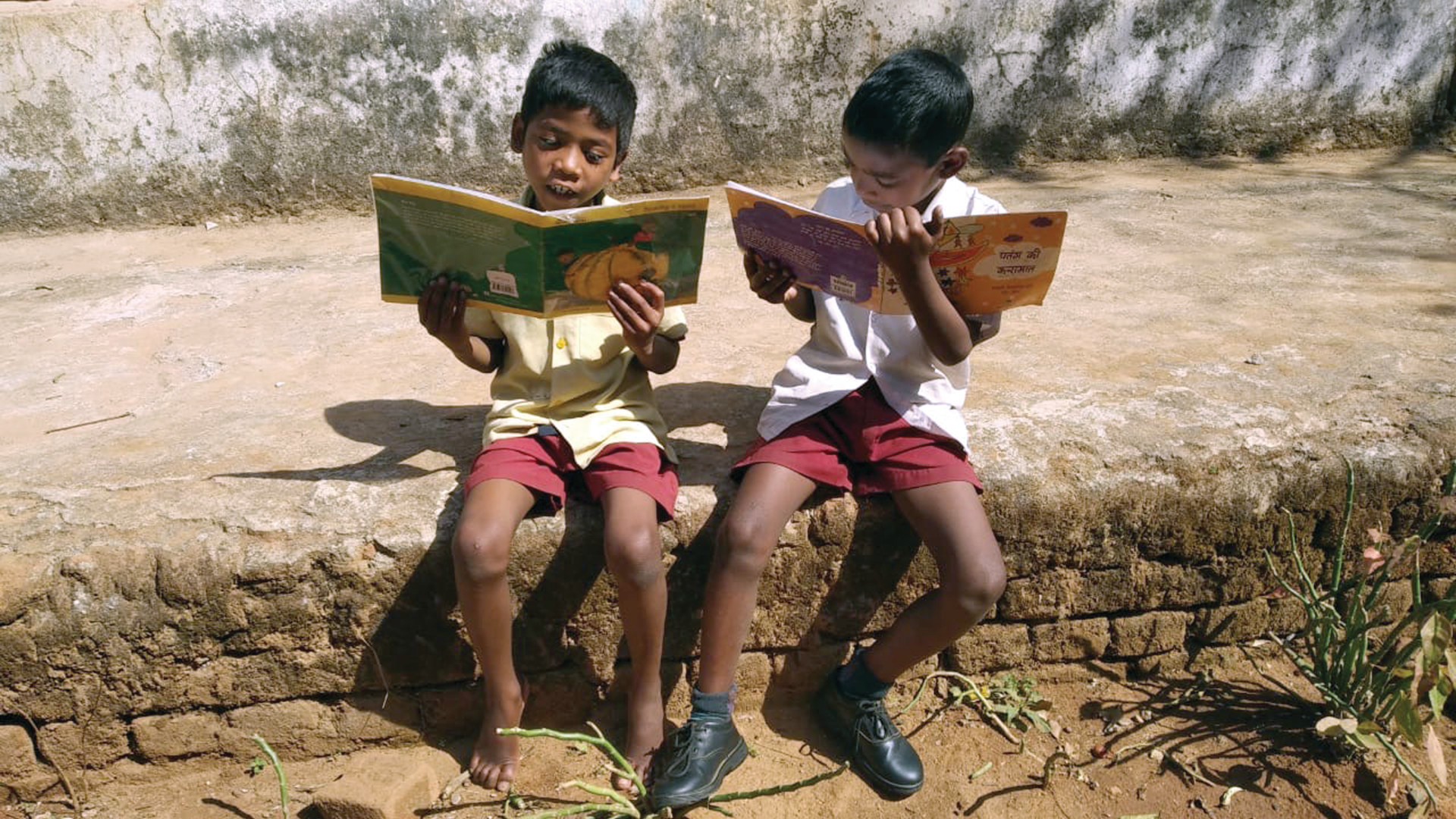

In 2011, the Trusts initiated a pilot project to advance reading among tribal schoolchildren. Most of these schools are in Khunti and a few of them in Hazaribag and East Singhbhum districts of the state. Implemented by the Collectives for Integrated Livelihood Initiatives (CInI), an associate organisation of the Tata Trusts, the programme has unfolded in full force since 2015. The objective is clear: enhancing the quality of learning and teaching in the region’s tribal-dominated government schools.

The programme’s starting point is the school itself. This involves setting up libraries, toilets and kitchen gardens — useful in feeding the ubiquitous midday meals scheme — the constitution of student councils, provision of learning aids and exposure to computers.

Training teachers

Teaching is central to the initiative, and the challenge here is immense. Jharkhand’s government schools face an endemic shortage of teachers. The Surunda village school in Khunti has two full-time teachers for its 146 students and that’s the common equation.

The state government has tried to deal with the lack by appointing ‘para-teachers’, who do almost all that is expected of regular teachers but are paid a lot less. The CInI initiative tackles the problem by training teachers and through the appointment of learning assistants, chosen from within the local community by village councils.

Teachers’ training by building their capacities and knowledge happens at the government’s ‘block resource centres’, where teachers can access learning material, interact with peers and attend pedagogy workshops.

The learning assistants — about 150 in the programme — have been invaluable in a situation where teacher deficits have undermined education outcomes. Their salaries are taken care of by CInI and their inputs are essential. At the school in Kudapurti village (Khunti), for instance, there are no government teachers for the 8th, 9th and 10th classes for more than 6 years, and the gap is filled by learning assistants.

Neeraj Pathak, the government teacher at the Kujrang school, located in the hilly countryside, says, “The learning assistant here is a big help. He’s a local and knows the Mundari language, which means he can communicate with the children and get them on the way to learning Hindi.”

Tapping tribal talent in hockey and academics

Priyanka Kumari wants to play hockey for India — “That’s my big dream,” she says — and she could well do that if she keeps up the hard work she is putting in as one of those selected for coaching at the ‘regional development centre’ (RDC) set up in Khunti as part of the Tata Trusts’ education programme in Jharkhand.

Priyanka is one of 30 girls and as many boys who have been fast-tracked for progress at the two RDCs —the other is in Simdega district — established by the Trusts to tap budding talent in a region with a rich crop in the sport. These kids, in the 13-15 age group, were chosen after a rigorous selection process.

The Trusts also have a grassroots hockey initiative in the state, involving about 5,300 children from 79 tribal-dominated schools. They organise interschool events and hockey festivals, and there’s a ‘training the trainer’ component too, where coaches are picked after trials involving experts from Bovelander & Bovelander BV, set up by Dutch hockey legend Floris Jan Bovelander.

Hockey aside, the education programme in Jharkhand is triggering academic aspirations through an initiative for deserving tribal children from poor backgrounds. Called the ‘super 30’ scheme, it has 30 girls and 30 boys from classes XI and XII, selected after a screening process, who are preparing — with expertise from the Avanti coaching centre in Khunti — to crack India’s ultra-competitive national engineering entrance examinations.

Mary Shreya, a 16-year-old from Khunti’s Bazzar Tanr village, is among the chosen ones. “I want to be a mechanical engineer, and I want to make it to the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay,” she says. Why Bombay? “I’ve heard so much about the city; it would be perfect.”

Parental supervision

The school management committees (SMCs), consisting mostly of parents, are the link between the community and school. They measure — and pressurise — the schools to live up to their promise by tracking the punctuality of students and teachers, cleanliness of the institution, quality of midday meals and, not least, the amount and efficacy of learning that takes place.

Says Raja Daud Mundu, president of the Surunda SMC, “Earlier, the teaching was erratic; that has changed. We want to make the school better. We need more teachers, one for each class, and we need better infrastructure.”

Out of the ordinary

The state’s education department is a willing and active partner in the programme, and its officials acknowledge CInI’s efforts. “The support we are getting has been commendable, as is the innovative nature of the work being done and the community mobilisation that is happening,” says Suresh Chandra Ghosh, superintendent of education, Khunti district. “The main contributions have been in mitigating teacher shortage, focusing on the quality of education delivered and in easing the language issue teachers from outside the tribal belt face when coping with children who know only the Mundari language.”

In quantifiable outcomes, Khunti has scored high. A recent central government survey of 117 ‘aspirational districts’ in India placed Khunti in second place on educational parameters. The Trusts and CInI, though, are not about to rest on such laurels. They are now advocating with Jharkhand’s education department to plug into the programme’s good practices and have them adopted across the state. It could mean giving children the opportunity to blossom!