Mar 3, 2019 | 670 words | 3-min read

Jamsetji Tata wrote to Swami Vivekananda in which he recalled his conversation with him and shared his project of setting up a science research institute in India. Transcript:

23 November, 1898

Esplanade House, Bombay.

Dear Swami Vivekananda,

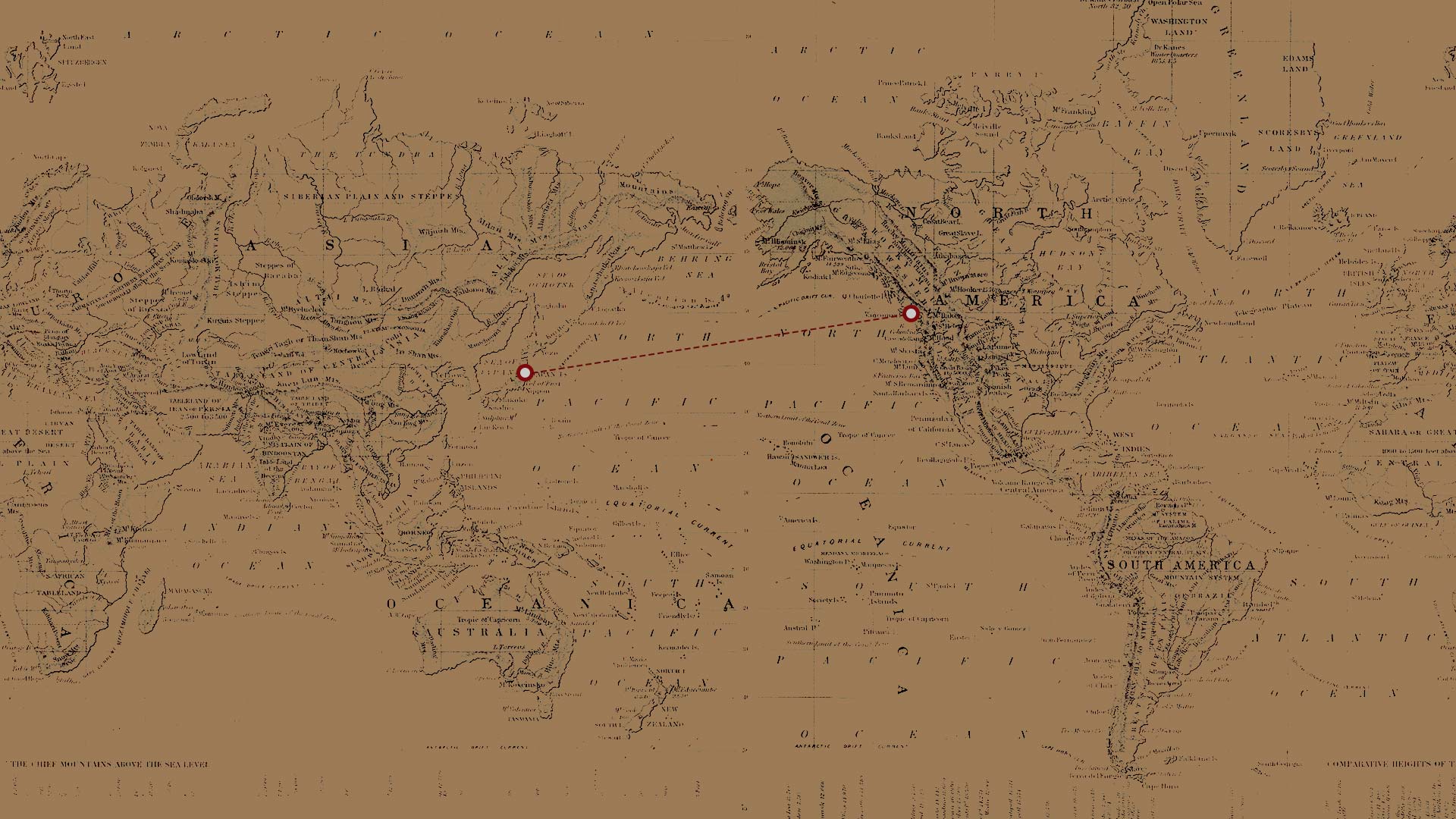

I trust you remember me as a fellow-traveller on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India, and the duty, not of destroying, but of diverting it into useful channels.

I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of a Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read. It seems to me that no better use can be made of the ascetic spirit than the establishment of monasteries or residential halls for men dominated by this spirit, where they should live with ordinary decency, and devote their lives to the cultivation of sciences – natural and humanistic. I am of opinion that if such a crusade in favour of an asceticism of this kind were undertaken by a competent leader, it would greatly help asceticism, science, and the good name of our common country; and I know not who would make a more fitting general of such a campaign than Vivekananda.

Do you think you would care to apply yourself to the mission of galvanising into life our ancient traditions in this respect? Perhaps, you had better begin with a fiery pamphlet rousing our people in this matter. I should cheerfully defray all the expenses of publication.

With kind regards,

I am dear Swami

Yours faithfully

Jamsetji N. Tata

The letter written by Swami Vivekananda in April I899 in Prabuddha Bharata, a monthly magazine started by him in 1896:

“We are not aware if any project at once so opportune and so far-reaching in its beneficent effects was ever mooted in India, as that of the post-graduate research university of Mr Tata. The scheme grasps the vital point of weakness in our national well-being with a clearness of vision and tightness of grip, the masterliness of which is only equalled by the munificence of the gift with which it is ushered to the public.

It is needless to go into the details of Mr Tata’s scheme here. Every one of our readers must have read Mr Padsha’s lucid exposition of them. We shall try to simply state here the underlying principle of it. If India is to live and prosper and if there is to be an Indian nation which will have its place in the ranks of the great nations of the world, the food question must be solved first of all. And in these days of keen competition it can only be solved by letting the light of modern science penetrate every pore of the two giant feeders of mankind: agriculture and commerce.

The ancient methods of doing things can no longer hold their own against the daily multiplying cunning devices of the modern man. He that will not exercise his brain, to get out the most from nature, by the lease possible expenditure of energy must go to the wall, degenerate and reach extinction. There is no escape. Mr Tata’s scheme paves the path placing into the hands of Indians this knowledge of nature — the preserver and the destroyer, the ideal good servant as well as the ideal bad master — that by having the knowledge, they might have power over her and be successful in the struggle for existence.

By some the scheme is regarded as chimerical, because of the immense amount of money required for it, to wit about 74 lacs. The best reply to this fear is: If one man — and he not the richest in the land — could find 30 lacs, could not the whole country find the rest? It is ridiculous to think otherwise, when the interest sought to be served is of the paramount importance.

We repeat: No idea more potent for good to the whole nation has seen the light of day in modern India. Let the whole nation therefore, forgetful of class or sect interests, join in making it a success.